| Twenty-some years ago, my sister Janet and I signed up for a field trip sponsored by the Crystal Cathedral to a Vedanta monastery in the nearby Saddleback Mountains. At that time we were working together on a discernment newsletter called “The New Age Alert” and attended as part of our research. The field trip was being promoted as an educational adventure to examine the similarities and differences of two supposedly opposite extremes of religious expression. The tour guide was a lady who was a long-time member of Robert Schuller’s Crystal Cathedral and she introduced herself as an aficionado of comparative religions. |

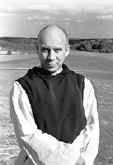

| The day started with a guided tour of the Crystal Cathedral grounds after we all met up at the statue of Job in the courtyard. Then after the tour of the most decadent ostentatious so-called house of God on the planet (that’s another story altogether), we boarded buses that took us on a short jaunt to the nearby wilderness. A man with a shaved head, in a red robe, with a blank look on his face greeted us. He told us not to concern ourselves with the fact that we would be ignored by all the Vedanta monks because they are in silence. The red-robed automatons kept at their work on the beautiful grounds of this gated cloister, without glancing in the direction of this group of mostly trendy Orange County housewives walking past. The blank stares on the faces of these men were a bit unnerving for Janet and me. They gave us the creeps, quite frankly. Their expressions remind me of the cult leader who led his thirty-nine followers to suicide to catch a ride on the Comet Hale-Bopp some ten years later. The “holy man” who was our guide to the grounds led us into a beautiful den with a fireplace and a large mahogany desk upon which a vase of freshly-cut flowers had been placed. The room was filled with books in built-in shelving and the furnishings looked like a blast from the past of a bygone era. We stood around in a circle as the monk gave us the history of the den. He told us that this was the retreat of a famous author named Aldous Huxley. Huxley had waited out World War II there as a place to get away from it all and as he tried unsuccessfully to establish a religious college there. “‘After seven years, he turned the property over to the Vedanta Society,” according to a published report in the July 15, 2006 issue of the New York Times. ”’They were trying to combine Eastern and Western philosophy and religion, but were ahead of their time,’’ said Swami Tadatmananda, 70, who leads the monastery.” The monk pointed to a book that was on a side-table that was next to me and said that it was one that Huxley wrote while he was there. I asked if I could pick it up and he nodded. I can’t recall the title, but the weirdest thing happened when I opened it. It was as if some evil spirit shot out of it and encircled the room. As it did, everyone’s stomachs rumbled loudly, one right after another, except for Janet’s and mine. Janet confirmed that she too could detect the swirling presence of this thing – it was felt, not actually seen. At that point all the Orange County housewives got uncomfortable because of their noisy tummies and we all made a hasty retreat out of that haunted den. At that time, I didn’t know who this Aldous Huxley guy was. However, his name would crop up from time to time in my investigations of the rising New Age Movement in the decade of the ‘80s. Many good Christian books were written exposing the dangers of new age influences in the church and by the decade of the ‘90s, born-again believers were pretty-much inoculated against eastern mysticism. Huxley’s Influence on Thomas Merton But now in the decade of the 00s, the latest craze in the church today, known as the Emergent Church/Conversation, is bringing a revival of mysticism into Evangelicalism. These EC leaders write books quoting the very mystics like Huxley who in the past sought God in all the wrong places. These books point Christians to the mystical practice of what is called contemplative/centering prayer that was popularized by one of Huxley’s contemporaries, the late Thomas Merton. Merton was a Roman Catholic Trappist monk and a anti-war peace activist during the Vietnam war. He was a prolific writer who coined the term “centering prayer” to describe the style of mind-emptying meditation that seeks to empty oneself and lose oneself into the void he interchangeably calls “the life of the spirit” and Nirvana. He held to the belief that all religions had the same basic truth and Christianity could not lay claim to the whole counsel of God. This put him on shaky ground in his own religion that professes to be the “one true church.” One Merton biographer traces Merton’s affection for mysticism to Huxley. “”Merton’s attraction to Asia developed gradually. The first concrete evidence of it dates back to November 1937, when he had come under the influence of Aldous Huxley. Since the 1930s Huxley, formerly a skeptic, had been attracted to mysticism and investigated Christian as well as Hindu and Buddhist mysticism. His newly acquired mystical views found expression in Ends and Means (1937), which Merton read at the suggestion of Robert Lax…. Huxley not only aroused in Merton an interest in mysticism but also drew his attention to the resemblances in the experiences of eastern and western mystics. In particular, Huxley pointed out similarities in the views of the anonymous author of the Cloud of Unknowing and of Meister Eckhart with those of the Buddha and India’s foremost philosopher, Sankara.” [Thomas Merton and Asia: His Quest for Utopia, by Alexander Lipski — ©1983, Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, page 5.] In Merton’s own words, he held this occultist in high esteem. From his own journal entry of November 27, 1941, Merton wrote, “I spent most of the afternoon writing a letter to Aldous Huxley and when I was finished I thought: ‘Who am I to be telling this guy about mysticism?’ I reflect that until I read his book, Ends and Means, four years ago, I had never even heard of the word mysticism. The part he played in my conversion, by that book, was very great. . . . Ends and Means taught me to respect mysticism. Maritain’s Art and Scholasticism was another important influence, and Blake’s poetry. . . . Anyway, what do I know to tell Huxley? I should have been asking him questions.” [The Secular Journal of Thomas Merton, ©1959, Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, New York, pp. 268-269]. The one thing these two men had in common was an interest in mysticism and the occult and both studied eastern religions to learn their techniques of crossing over to the other side, as it were. They opened many a door to evil spirits who gave them the mystical experiences they longed for. The Hindu holy men that they so admired are of the sort you might see on TV programs such as “Mysteries of the Unknown” – the guys sitting on beds of nails or piercing their cheeks with steel knives without feeling any pain. And Merton was so fascinated by these “holy men” that he even adopted the name “Rabbi Vedanta” as an alias. Several months before his death, he wrote to a friend in California, “There will come some mail for me there probably between now and 30th. This will include a mysterious and mystic package addressed to Rabbi Vedanta, care of you. Have no fear. ‘Tis only I under the beard.” [The Hidden Ground of Love: The Letters of Thomas Merton, edited by William H. Shannon, ©1985 Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, p. 243]. Merton’s friendship with Huxley spanned several decades, up until Huxley’s death on November 22, 1963, the same day that President Kennedy was assassinated and on the same day that C. S. Lewis died. As Merton’s interest in eastern philosophy grew, he would keep his friend Huxley up-to-date. In a letter dated November 27, 1958, Merton wrote to his friend taking issue with his observation that the use of psychedelics could be a shortcut to transcendental experiences. “May I add that I am interested in yoga and above all in Zen, which I find to be the finest example of a technique leading to the highest natural perfection of man’s contemplative liberty. You may argue that the use of a koan (a puzzle with no logical solution used in Zen Buddhism to develop intuitive thought) to dispose one for satori (a spiritual awakening sought in Zen, often coming suddenly) is not different from the use of a drug. I would like to submit that there is all the difference in the world, and perhaps we can speak more of this later. My dear Mr. Huxley, it is a joy to write to you of these things.” [Hidden Ground, p. 439.] Sufi Mysticism By now you can see that Merton was a believer in all religions – he created his own syncretistic brand of religion while remaining under the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. He gave equal attention to the mystical traditions within Catholicism, Zen Buddhism, and Hinduism. But he was an equal-opportunity mystic who was drawn to the common thread of “Satan’s so-called deep secrets” found in all the world’s false religions, including his own. He even delved into the mystical branch of Islam and corresponded for many years with a Muslim Sufi cleric by the name of Abdul Aziz. In November, 1960, Aziz had requested that Merton send him one of his books called Seeds of Contemplation that he wrote in 1949, but Merton was too ashamed to send it to him. He apologized to his Sufi friend saying that it “contains many foolish statements…and reflects an altogether stupid ignorance of Sufism.” At that time Merton thought that true spirituality existed only in the Roman Catholic Church. But as he toyed with other religions, they soon got a grip on his mind and soul. In the same letter to Aziz dated November 17, 1960, Merton offered the Sufi information on whom he considered Catholicism’s number one mystic. He wrote, “I might also refer you to the life of St. John of the Cross… which has some interesting pages on the possible influence of Sufism in the mysticism of St. John of the Cross.” [Hidden Ground, p. 44.] Merton also made the claim that the Sufi mystics worship the same God as Christianity and all the religions. He wrote, “As one spiritual man to another, if I may so speak in all humility, I speak to you from my heart of our obligation to study the truth in deep prayer and meditation, and bear witness to the light that comes from the All-Holy God into this world of darkness where He is not known and not remembered. . . . May your work on the Sufi mystics make His Name known and remembered, and open the eyes of men to the light of His truth.” [Ibid, pp. 45-46]. Merton believed that the Sufi, Zen, and Vedanta monks all shared in the same light as he did – and I’m sure that is the case. After all, Satan comes as an angel of light and they all recognized that same “light” in one another. Merton even went so far as to redefine the feast of Pentecost to suit the sensitivities of this Sufi cleric. In a letter dated May 13, 1961, Merton wrote to Aziz, I will “keep you especially in mind on the feast of Pentecost, May 21st, in which we celebrate the descent of the Holy Ghost into the hearts and souls of men that they may be wise with the Spirit of God. It is the great feast of wisdom.” [Ibid. p. 49] Merton actually believed that these men who worshiped false gods were given some great wisdom by God and that Pentecost is a holy day to celebrate a feast of wisdom given to all men irregardless of what God one puts faith in. Merton confided in Aziz what he actually believed, knowing that his own church authorities would probably not approve if they knew just how far he took it. In his January 2, 1966 letter to the Sufi cleric, Merton revealed his heretical ideas of an impersonal God. “My prayer is then a kind of praise rising up out of the center of Nothing and Silence. If I am still present ‘myself’ this I recognize as an obstacle about which I can do nothing unless He Himself removes the obstacle. If He wills He can then make the Nothingness into a total clarity. If He does not will, then the Nothingness seems to itself to be an object and remains an obstacle. Such is my ordinary way of prayer, or meditation. It is not ‘thinking about’ anything, but a direct seeking of the Face of the Invisible, which cannot be found unless we become lost in Him who is Invisible. I do not ordinarily write about such things and I ask you therefore to be discreet about it. But I write this as a testimony of confidence and friendship. It will show you how much I appreciate the tradition of Sufism. . . . I am united with you in prayer during this month of Ramadan (Muslim holy day) and will remember you on the Night of Destiny.” [Ibid. p. 64.] Another Way to Perfection Merton was a prolific writer which was partly due to his isolation in a Trappist monastery in Kentucky where his fellow monks held to vows of silence. But Merton had a lot to say and he couldn’t share it with his fellow monks, so he corresponded with religious leaders, including his friend the Dali Lama, a man that many Buddhists believe to be an ascended master. Merton biographer Alexander Lipski wrote that “Merton argued that Zen meditation shatters the false self and restores us to our paradisical innocence which preceded the fall of man.” [Thomas Merton and Asia: His Quest for Utopia by Alexander Lipski — ©1983, Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, MI, page 29.] Can Zen Buddhism really restore mankind to the innocence that Adam and Eve enjoyed in the Garden of Eden? If that were possible, then such men could not die, because when Adam and Eve ate of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, death entered into the human race. This claim is tantamount to saying that Zen meditation is the means for spiritual perfection and justification, totally stepping on the blood of Christ. Thomas Merton might have truly committed the unpardonable sin with this heretical belief. “For it is impossible for those who were once enlightened…and have become partakers of the Holy Spirit, and have tasted the good word of God and the powers of the age to come, if they fall away, to renew them again to repentance, since they crucify again for themselves the Son of God, and put Him to an open shame. For the earth which drinks in the rain that often comes upon it, and bears herbs useful for those by whom it is cultivated, receives blessing from God; but if it bears thorns and briars, it is rejected and near to being cursed, whose end is to be burned” (Hebrews 6:4-8). “Of how much worse punishment, do you suppose, will he be thought worthy who has trampled the Son of God underfoot, counted the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified a common thing, and insulted the Spirit of grace?” (Hebrews 10:29). How many people today who have a fascination for the writings of Thomas Merton run the risk of following him into perdition? Poet/Artist William Blake Merton’s philosophy in life can be seen clearly in his admiration of the poet and artist William Blake (1757-1827). Scripture did not enter into Merton’s search for experiencing the Divine; it was not sufficient for him. In fact, I have read all of his journals and can count on one hand the Bible verses he quoted. The Word of God did not factor into Merton’s life. He was basically a humanist who worshipped imagination and human reasoning. William Blake influenced Merton’s choice of Catholicism as the organizational structure in which to live out his brand of spiritualism. Merton biographer Raymond Bailey documented how this took place. “An important link in Merton’s thought is the work of his master’s thesis, written in 1938. It was a study of William Blake, whose ideas influenced both his theology and his poetry. . . . Tom said that it was through Blake that he had come to the Church and to Christ. The thesis was an exposition of Blake’s philosophy; indeed, it was an apologetic for the poet’s Christianity. ‘As mystic,’ Merton argued, ‘Blake belongs to the Christian tradition of the Augustinians and the Franciscans.’ Already Merton was cognizant of similarities between Christian and oriental mysticism. He called attention to Blake’s acquaintance with Hindu philosophy. He drew attention to ideas common to Blake and Meister Eckhart, in whose thought Merton was to develop a vital interest during the sixties. [Thomas Merton on Mysticism by Raymond Bailey, ©1974, Doubleday & Co., Inc, Garden City, NY, p. 44.] And yet both Blake and Eckhart were steeped in the occult and got their mysticism from Hindu sources. Eckhart’s ideas were considered heretical even by Catholic Church authorities because his teachings expressed a belief in pantheism. And Blake’s poetry is some of the darkest and most demonically inspired drivel one could read. Like attracts like, no doubt. Perhaps that is why the demonized lead singer of the 60s group, The Doors, Jim Morrison, named his group after one of Blake’s poems and chose dark sayings of Blake’s to use in one of his songs. The Door’s Jim Morrison “Its name was taken from Aldous Huxley’s book on mescaline, The Doors of Perception, which quoted William Blake’s poem, “If the doors of perception were cleansed / All things would appear infinite.” Morrison identified with Blake and “famously lived by an oft repeated quote from William Blake: ‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.’” “Morrison once confessed that ‘We’re more interested in the dark side of life, the evil thing, the night time.’” The last two lines of a Blake poem were incorporated into The Doors 1967 song, “End of the Night.” Every morn and every night A former girlfriend of Morrison’s gave some insights to his fascination with William Blake. In the late 60s, she used to go out to the desert with him to use peyote and see strange visions. Morrison had believed that the spirit of a dead Indian shaman inhabited his soul and he connected to the spirit out there in the desert. “We had visions in the desert,” she wrote of her and Morrison’s experiences in a book called “An Unholy Alliance.” “It is like William Blake; he would see visions like Blake did, angels in trees, he would see these, and so would I. And Jim showed me that this is what a poet does. A poet sees visions and records them.” Merton recognized that Blake communed with angels, though he would not come right out and admit that they were fallen angels. Merton had written a Forward to a book about, of all things, wooden furniture made by the Shakers religious sect. He wrote, “The peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is due to the fact that it was made by someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it. Indeed the Shakers believed their furniture was designed by angels – and Blake believed his ideas for poems and engraving came from heavenly spirits.” [Religion in Wood: A Book of Shaker Furniture by Edward & Faith Andrews, Introduction by Thomas Merton. ©1966 Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, pg xiii]. Same Vocabulary; Warped Definitions Both men confused the gifts of the Holy Spirit for man’s natural talents and through the use of the imagination, they were exercising their gifts. Merton wrote in the Shaker book, ‘When imagination, art and science and all intellectual gifts, all gifts of the holy Ghost are looked upon as of no use, and only contention remains to man, then the Last Judgment begins … For Blake, as for the Shakers, creative imagination and religious vision were not merely static and contemplative. They were active and dynamic, and imaginative power that did not express itself in creative work could become highly dangerous.” [Ibid. pg. xiv] Besides getting Pentecost and the filling of the Holy Spirit wrong, Merton also distorted the meaning of the new birth. He accepted the false religious systems of the world and adopted their corruption of Christian doctrines. Merton wrote to a Sufi cleric in a letter dated March 22, 1968, “I also enclose a copy of something I wrote last fall ‘Rebirth and the New Man in Christianity,’ which will show that I was already in complete agreement with you. It may also give you some introduction to the idea of rebirth which is so important in Christianity – just as it is in Sufism.” [Hidden Ground, p. 42]. Merton admitted that venturing into the recesses of the mind via contemplative methods could be highly dangerous because it led to a dark and foreboding place. In a letter written to the abbot of a Cistercian monastery, Merton said, “My brother, perhaps in my solitude I have become as it were an explorer for you, a searcher in realms which you are not able to visit – except perhaps in the company of your psychiatrist. I have been summoned to explore a desert area of man’s heart in which explanations no longer suffice, and in which one learns that only experience counts. An arid, rocky, dark land of the soul, sometimes illuminated by strange fires which men fear and peopled by specters which men studiously avoid except in their nightmares.” [Hidden Ground, pp. 156-157.] When Merton said that “explanations no longer suffice,” he no doubt was referring to Bible doctrine that he didn’t see as sufficient. In that same letter he said that he distrusts the language of Christianity. And what are those “specters” and “strange fires” he says he encounters? When Merton could find no Bible teaching to endorse his experiences, he quit looking there for answers and turned to other religions. Some things never change. This perceived inadequacy of the Word of God drives many unregenerate professing Christians to other places for their reassurance. Merton is consistent in his descriptions of his spiritual path’s dark side. He wrote a fellow pacifist on February 13, 1967, telling him about his spiritual experimentation using tongue-in-cheek humor, but getting his message across quite clearly. He wrote, “I guess my head is so addled with Zen and Sufism that I have totally lapsed into inefficiency, and am rapidly becoming a backward nation if not a primitive race, a Bushman from the word go, muttering incantations to get the fleas out of my whiskers, a vanishing American who has fallen into the mythical East as into a deep dark hole.” [Hidden Ground, p. 299] From Eckhart to Blake to Huxley to Morrison and to Merton, the common denominator they all shared was a metaphysical experience, via Kundilini or psychedelic drugs that were a shortcut to the same dark place. And tragically Merton influenced so many young minds when he was alive and his influence continues to poison professing Christians to this day. People are unknowingly opening doors to the evil influences of demonic hosts. Merton Continues to Corrupt One newspaper published an article about Merton in 1998. “Thirty years later, what Merton has given to his countless spiritual devotees has never stopped; through his books and books about him, Merton might exert more global influence than ever.” [“30 Years After His Death, Noted Monk Thomas Merton is Remembered,” By Art Jester, Knight Ridder Newspapers, December 12, 1998.] Merton’s writings are quoted by today’s advocates of his contemplative prayer methodology that he derived from dark sources as already documented. Look in the notes of any modern book on prayer, and see if you find Merton quotes. This leaven of doctrines of devils has found its way into such popular “Evangelical” books as Richard Foster’s Celebration of Discipline and Brennan Manning’s, Ragamuffin Gospel, books that grace the shelves of many church bookstores. Chuck Smith Jr., pastor of Capo Beach Calvary (though he’s no longer affiliated with Calvary Chapel, the movement founded by his father Chuck Smith Sr., but still retains the name), often quotes Merton in his own sermons, such as in his March 12th 2006 message, “It Is Enough.” In fact, a woman who attends Capo Beach Calvary wrote this writer an email on March 17, 2006 singing the praises of the men her pastor admires. “I also thoughtfully enjoy the writings of Thomas Merton, Brennan Manning (that great ragamuffin!) and of course the writings of Richard Foster! These men have something worth listening to. Blessings, B.” She seemed to get pleasure in rubbing my nose in the success of the apostasy. In fact, a common term used by Emerging Church leaders like Chuck Smith Jr. is the word “transformation.” This word is thrown around a lot by today’s contemplatives in a way to distort the Bible teaching of being transformed into the image of Christ. “For whom He foreknew, He also predestined to be conformed to the image of His Son, that He might be the firstborn among many brethren” Romans 8:29. “And do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is that good and acceptable and perfect will of God” Romans 12:2. Yet, here’s how Merton and contemplatives who emulate him see the use of the word transformation: “While considering certain external imitations of Zen unsuitable for westerners, Merton, to the end of his life, believed that the transformation of personal consciousness through Zen would bring about a more equitable, peaceful society.” [Utopia, pp. 35-36.] So it is through Zen meditation that Merton and his breed achieve this transformation of their consciousness that amounts to a new age paradigm shift right out of the confines of Christianity. Another Merton biographer described it this way: “This ancient Christian method, as it was taught and shared in this renewal, received a new packaging and a new name. The name given it was Centering Prayer, a name inspired by Father Louis’s (Merton’s real first name) teaching. In speaking about this kind of prayer, he would say things such as this: ‘The fact is, however, that if you descend into the depths of your own spirit…and arrive somewhere near the center of what you are, you are confronted with the inescapable truth, at the very root of your existence, you are in constant and immediate and inescapable contact with the infinite power of God.’ And like this: ‘A man cannot enter in to the deeper center of himself and pass through the center into God unless he is able to pass entirely out of himself and empty himself and give himself to other people in the purity of selfless love.’” [Thomas Merton Brother Monk: The Quest for True Freedom, by M. Basil Pennington, ©1987 Harper & Row, San Francisco, p. 160.] Another biblical sounding term Merton and other eastern contemplatives throw around is “incarnational.” Jesus was God incarnated in human flesh and this word is brandied about to sound biblical but the meaning of it changes to apply to those calling themselves Christians. Another biographer (seems Merton has an endless supply of them) put it this way: “For Merton conceives Christ as being at the center of the universe and hence, it is in Christ and only in him that the world can truly make sense. Because everything converges on Him, the person most closely related to Christ in contemplative prayer is, in Merton’s view, the person who is most deeply embedded in the world. For such a person is no longer limited by narrow provincial views (Bible views?) … Rather, detached from such superficiality because of his own closeness to Christ, he is …thus is able to find a truly incarnational involvement that will bring him into the deepest contact with reality.” [Merton’s Theology of Prayer by John J. Higgins SJ ©1971, Cistercian Publications, Spencer, MA, p. 125.] The “Christ” Merton speaks of is not Jesus Christ of the Gospels since Merton’s “Christ” is accessible to anyone in any religion at any time of their choosing. This Cosmic Christ is what the Bible refers to “another Christ.” Merton’s quest for the so-called undiluted reality of Zen was a liberation from all “structures, forms, and beliefs,” that brings one to the true transcendent self of Buddhism. In other words, Merton hated the very form of religion that held him in Catholicism, but was in bondage to the security he got from the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani where he could live and write in isolation without having to think about how he might make an honest living. Merton’s tone with Catholic authorities was guarded, totally different from his openness with his eastern religious friends. Merton Grovels Before Popes Two letters to two different popes were preserved and published. No hint of his eastern proclivities were revealed to either of them. In the November 10, 1958 letter to Pope John XXIII, Merton begins his letter with the words, “My dear Holy Father: This is one of you children who comes to kneel at your feet…” In this letter, Merton quotes scripture – something he rarely ever does. He wrote, “Humbly prostrating ourselves before Your Holiness, my novices and I beg you to grant us the favor of your Apostolic Blessing, so that we may be holy monks and deeply fervent priests, that we may unite in our hearts perfect contemplation and apostolic zeal and that Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who is the way, the truth and the life, may be known and loved by all. [The Hidden Ground of Love] And to Pope Paul VI, on July 26, 1963, after greeting the pope with “”Most Holy Father: Humbly prostrate at the feet of Your Holiness,” Merton wrote, “It will be my own devoted effort to help the novice to become true contemplative monks, men of God, totally devoted to the love and contemplation of Jesus Christ (one of the few times Jesus’ name is mentioned in his letters), and deeply concerned, at the same time, with all the interests of His Church in the troubled times in which we live.” [Ibid. p. 487.] Had Merton revealed what he was actually teaching the under-monks, the pope just might have stripped him of his hair shirt. Not long ago, a Catholic priest was excommunicated for promoting ideas of pantheism and the Cosmic Christ. His name was Matthew Fox and his main protagonist was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, better known today as Pope Benedict XVI. Another Merton biographer described just how far into error Merton went at the end of his life: “In his last years Merton became engrossed in the commonplaces of Eastern and Western mysticism. He was one of those for whom ‘ecumenical’ meant ‘worldwide or universal in extent and influence.’ His understanding of the unity of the world, a panentheistic God, and a cosmic Christ prohibited a narrowly defined humanity or limited theater of God’s action. The universality of the human quest for authentic being seemed to hold for him the potential for establishing a transcultural family of man.” [Merton on Mysticism, p. 15.] Is the Monk Catholic? There was a part of Thomas Merton that remained very Catholic: his attraction to icons and statues. He saw them as doorways to his contemplative invisible inner world. And his devotion to the Queen of Heaven, the many faces of Mary drew him as well. And yet even in this, he found a way to connect these facets of Catholicism to Eastern religions. On September 12, 1959, he wrote to his friend Czeslaw Milosz, one of Merton’s Catholic spiritual guides who shared his attraction for Buddhism, a letter that revealed his devotion to Mary: “Christ loves in us, and the compassion of Our Lady keeps her prayer burning like a lamp in the depths of our being. That lamp does not waver. It is the light of the Holy Spirit, invisible, and kept alight by her love for us.” [Striving Towards Being: The Letters of Thomas Merton and Czeslaw Milosz, edited by Robert Faggen, ©1997, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, p. 53.] In a letter dated January 30, 1961, he also told his Muslim Sufi friend about their mutual attraction to Mary: “Mary is believed to have appeared at a village in Portugal called Fatima: but this name certainly derives from the time when the area was under the Moslems and the village must have been named after the daughter of the Prophet. Hence there is a mysterious joining of Christian and Moslem elements in this devotion to Our Lady of Fatima.” [Hidden Ground, p. 48.] Merton’s attraction to icons far exceeded most Roman Catholic tradition. On December 5, 1965 he wrote to his friend Marco Pallis, a student of Tibetan art, religion and culture and author of the book Peaks and Lamas who had sent him a gift of an expensive icon of the “virgin and child” a common Catholic view of Jesus as a child subordinate to His mother. With the icon, Pallis wrote Merton a note, “Here is a small token of my love: this ikon . . . Your karma evidently wished you to receive it…the Mother of God…four saints in attendance.’ Merton responded: “Where shall I begin? I have never received such a precious and magnificent gift from anyone in my life. I have no words to express how deeply moved I was to come face to face with this sacred and beautiful presence granted to me in the coming of the ikon to my most unworthy person. At first I could hardly believe it. And yet perhaps your intuition about my karma is right, since in a strange way the ikon of the Holy Mother came as a messenger at a precise moment when a message was needed, and her presence before me has been an incalculable aid in resolving a difficult problem. . . . Let me return to the holy ikon. Certainly it is a perfect act of timeless worship, a great help. I never tire of gazing at it. There is a spiritual presence and reality about it, a true spiritual ‘Thaboric’ light, which seems unaccountably to proceed from the Heart of the Virgin and Child as if they had One heart, and which goes out to the whole universe. It is unutterably splendid. And silent. It imposes a silence on the whole hermitage…I see how important it is to live in silence, in isolation, in unknowing. There is an enormous battle with illusion going on everywhere, and how should we not be in it ourselves?” [Hidden Ground, p. 473-474.] One Orthodox online dictionary defines “The Taboric Light” as “the light that surrounded Christ in the Transfiguration, the goal sought in contemplation by the hesychasts, was a theophany, or manifestation of God, through His uncreated energies.” Merton tosses around terms like “Karma” and “Thaboric light” more than he ever quotes God’s revelation to man: the Bible. If any presence accompanied this icon, it surely wasn’t from God since He has forbidden the idolatry of religious idols such as this. Perhaps the Roman Catholic Church opened themselves up to such deceiving spirits by removing the second commandment out of their catechism. Invisible, but not Forgotten It is remarkable that elements within the church today would point to dead heretics such as Merton as a source for any kind of spiritual truth. The man was truly demonized and corrupted many undiscerning souls who no doubt are with him in hell to this day. And that brings us to the details of the untimely death of Louis “Thomas” Merton. Here is a chronology of the events leading up to Merton’s demise in his own words:

On December 10, 1968 Merton was in Bangkok, Thailand preparing to gather with local Buddhist monks. He got into the shower that had a fan above blowing on him, and he reached up and accidentally touched it and was electrocuted. He was 53-years-old. He reached the place in the afterworld that fascinated him so much in life. I seriously doubt that it impressed him once he arrived with no way out. Both he and a fellow monk had had premonitions that he would not be coming back from Thailand alive. “By a strange coincidence, it has been noted that he concluded his last conference in Bangkok with the words: | |

http://www.apostasyalert.org/Merton.htm